Proof that \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) is a vector space #

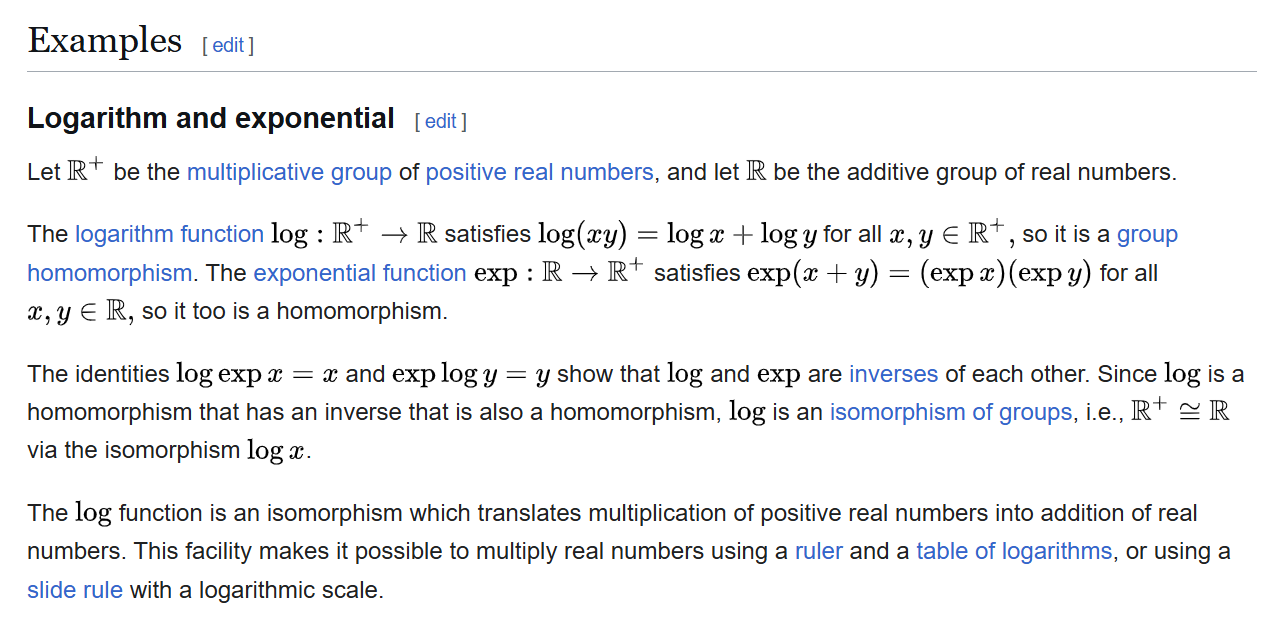

screenshot from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isomorphism#Logarithm_and_exponential

Statement #

Denote by \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) as the set of all vectors with one strictly positive real entry.

\[ \mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}=\left\{\begin{bmatrix}x\end{bmatrix}\in\mathbb{R}^{1}\mid x\in\mathbb{R}\land x>0\right\} \]Vector addition in \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) is defined as the following (\(\vec{\mathbf{u}},\vec{\mathbf{v}}\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\)):

\[\vec{\mathbf{u}}\oplus\vec{\mathbf{v}}=\begin{bmatrix}u_{1}v_{1}\end{bmatrix}\]\(u_{1}v_{1}\) means the first (and only) entry of \(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\) multiplied by the first (and only) entry of \(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\) (product of scalars).

Scalar multiplication in \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) is defined as the following (\(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) and \(c\in\mathbb{R}\)):

\[c\odot\vec{\mathbf{u}}=\begin{bmatrix}\left(u_{1}\right)^{c}\end{bmatrix}\]\(\left(u_{1}\right)^{c}\) means the first (and only) entry of \(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\) to the power of \(c\) (exponentiation of a strictly positive real number to a real power).

Prove that \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) is a vector space.

Proof using axioms #

A useful reference for these axioms can be found here.

- Closure under vector addition

- Closure under scalar multiplication

- Existence of zero vector

- Existence of negative vector

- Associative law for vector addition

- Commutative law for vector addition

- Distributive law for scalar multiplication over vector addition

- Distributive law for scalar multiplication over scalar addition

- Associative law for scalar multiplication

- Unity law for scalar multiplication

I’ll leave axioms 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 as an exercise for the reader (unless there is a request – feel free to contact me!).

Axioms 3 and 4 are interesting to consider.

Axiom 3 (existence of zero vector): there exists \(\vec{\textbf{0}}\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) such that \(\vec{\textbf{u}}\oplus\vec{\textbf{0}}=\vec{\textbf{u}}=\vec{\textbf{0}}\oplus\vec{\textbf{u}}\) for all \(\vec{\textbf{u}}\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\)

- The important realization here is that \(\vec{\textbf{0}}\) is \(\begin{bmatrix}1\end{bmatrix}\), not \(\begin{bmatrix}0\end{bmatrix}\).

Axiom 4 (existence of negative vector): for each \(\vec{\textbf{u}}\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\), there exists \(\vec{\textbf{v}}\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) such that \(\vec{\textbf{u}}\oplus\vec{\textbf{v}}=\vec{\textbf{0}}=\vec{\textbf{v}}\oplus\vec{\textbf{u}}\)

- Based on what we noted about \(\vec{\textbf{0}}\) in axiom 3, the important realization here is that \(\vec{\textbf{v}}\) is \(\begin{bmatrix}\frac{1}{u_{1}}\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\left(u_{1}\right)^{-1}\end{bmatrix}\), not \(\begin{bmatrix}-u_{1}\end{bmatrix}\). Note that \(\begin{bmatrix}\left(u_{1}\right)^{-1}\end{bmatrix}\) is equivalent to \(-1\odot\vec{\textbf{u}}\).

Proof using isomorphism from \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) onto \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\)[needs revision] #

Caution

This section may not be completely accurate and needs revision. Refer to https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/5070460/true-or-false-a-space-that-is-isomorphic-to-a-vector-space-must-also-be-a-vecto. Feel free to contact me if you are interested in improving this section.

Perhaps it’s more accurate to think of this section as “Proof that \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) is isomorphic to \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\), after we have established that \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) is a vector space.”

Define the transformation (or function or mapping) \(T\colon\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\to\mathbb{R}^{1}\) as \(T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(u_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}\) where \(w\) is an arbitrary strictly positive real number that is an element of \(\left(0,1\right)\cup\left(1,\infty\right)\). For example, it can be said without loss of generality that \(T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{e}\left(u_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\ln\left(u_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}\). To prove that \(T\) is an isomorphism from \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) onto \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\), we can prove that \(T\) is one-to-one (injective), onto \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\) (surjective), and linear.

To prove that \(T\) is one-to-one (injective), we can prove that if \(T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)=T\left(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\right)\), then \(\vec{\mathbf{u}}=\vec{\mathbf{v}}\).

\[T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)=T\left(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\right)=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(u_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(v_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}\] \[w^{\log_{w}\left(u_{1}\right)}=w^{\log_{w}\left(v_{1}\right)}\Rightarrow u_{1}=v_{1}\Rightarrow\vec{\mathbf{u}}=\vec{\mathbf{v}}\]To prove that \(T\) is onto \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\) (surjective), we can prove that for any \(\vec{\mathbf{x}}\in\mathbb{R}^{1}\), there exists \(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) such that \(T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)=\vec{\mathbf{x}}\).

\[T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)=\vec{\mathbf{x}}=\begin{bmatrix}x_{1}\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(u_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}\Rightarrow\vec{\mathbf{u}}=\begin{bmatrix}w^{x_{1}}\end{bmatrix}\]To prove that \(T\) is linear, we can prove that \(T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\oplus\vec{\mathbf{v}}\right)=T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)+T\left(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\right)\) and that \(T\left(c\odot\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)=cT\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)\) for all scalars \(c\in\mathbb{R}\).

\[T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\oplus\vec{\mathbf{v}}\right)=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\oplus\vec{\mathbf{v}}\right)_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(u_{1}v_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(u_{1}\right)+\log_{w}\left(v_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}\] \[T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\oplus\vec{\mathbf{v}}\right)=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(u_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}+\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(v_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}=T\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)+T\left(\vec{\mathbf{v}}\right)\] \[T\left(c\odot\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(\left(c\odot\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(\left(u_{1}\right)^{c}\right)\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}c\log_{w}\left(u_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}\] \[T\left(c\odot\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)=c\begin{bmatrix}\log_{w}\left(u_{1}\right)\end{bmatrix}=cT\left(\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)\]In the proof of linearity above, be cautious to properly keep track of whether a vector is in \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) or \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\).

Therefore, \(T\) is an isomorphism from \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) onto \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\). Because an isomorphism exists from \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) onto \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\), the space \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) is isomorphic to \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\) (\(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\cong\mathbb{R}^{1}\)).

Since \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\cong\mathbb{R}^{1}\) and \(\mathbb{R}^{1}\) is a vector space, we can conclude that \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\) is a vector space.[needs revision]

Miscellaneous #

\[c\odot\vec{\mathbf{u}}=\begin{bmatrix}\left(u_{1}\right)^{c}\end{bmatrix}\Rightarrow c=\log_{u_{1}}\left(\left(c\odot\vec{\mathbf{u}}\right)_{1}\right)\]For any \(\vec{\mathbf{w}}\) such that \(w_{1}\in\left(0,1\right)\cup\left(1,\infty\right)\) and any \(\vec{\mathbf{x}}\in\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\), we can find a scalar \(c\) such that \(c\odot\vec{\mathbf{w}}=\vec{\mathbf{x}}\). Therefore, \(c\odot\vec{\mathbf{w}}\) spans \(\mathbb{R}_{>0}^{1}\). Since there is \(1\) basis vector, the dimension of the vector space is \(1\).

References #

https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/1332747/proof-that-mathbbr-is-a-vector-space

https://www.stat.uchicago.edu/~lekheng/courses/110f07/math110-hw1sol.pdf

https://www.math.stonybrook.edu/~scott/mat310.spr05/docs/LogAsIsomorphism.pdf

https://sites.lafayette.edu/thompsmc/files/2015/12/HW7_2_Key.pdf

http://matematika.reseneulohy.cz/2504/the-space-of-positive-real-numbers

https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Definition:Strictly_Positive/Real_Number

https://math.emory.edu/~lchen41/teaching/2020_Fall/Section_7-3.pdf

David Clark Lay, Steven Ramer Lay, Judith Joanne McDonald. Linear Algebra and Its Applications. Pearson. 5th edition, 2016. ISBN-13 9780321982384. ISBN-10 032198238X.